WASHINGTON — A cubesat launched as a secondary payload on Artemis 1 may end its operations at the end of the month unless it can get its propulsion system working.

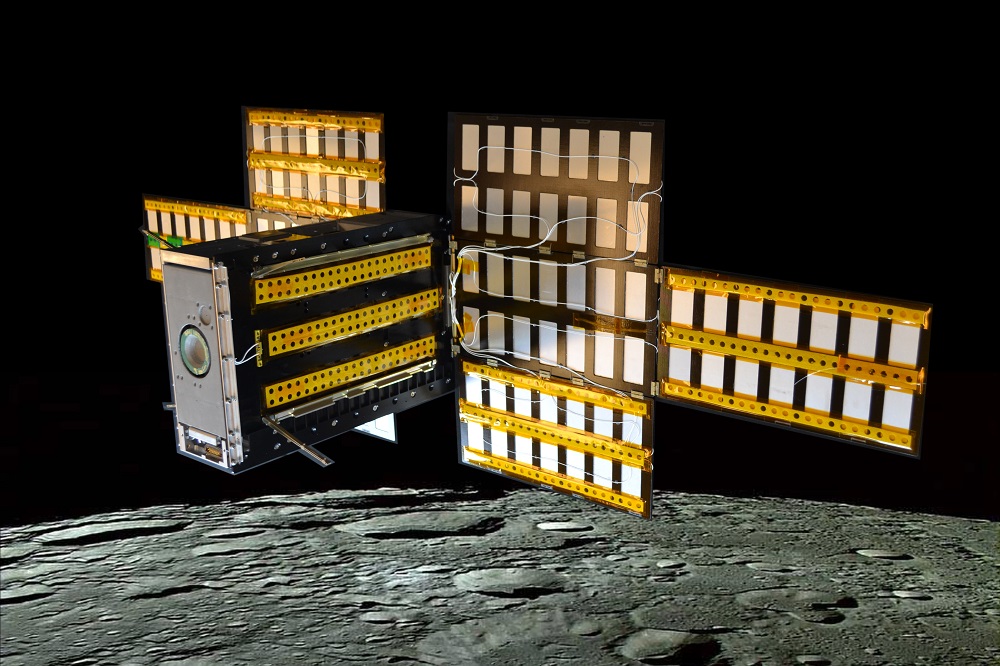

The LunaH-Map spacecraft was one of 10 cubesats launched as secondary payloads on the inaugural flight of the Space Launch System last November. The spacecraft had planned to use an ion propulsion system on the 6U cubesat to perform a maneuver as it flew by the moon days later, ultimately allowing it to go into orbit.

That thruster, though, failed to fire because of what engineers believe is a stuck valve. In a presentation at the Interplanetary Small Satellite Conference May 1, Craig Hardgrove, principal investigator for the mission at Arizona State University, said the project had anticipated problems with it given the long delay between the spacecraft’s delivery to NASA in mid-2021 and its November 2022 launch.

“We had informed NASA that this propulsion system was not built to withstand a long launch delay, longer than four or five months,” he said, but there was no way to access the cubesat once the Orion spacecraft was mated to the stage adapter where the cubesats were mounted in the fall of 2021.

The thruster, a BIT-3 from Busek, uses iodine as propellant, and Hardgrove said engineers expected that iodine may have vaporized during the long wait, getting into valves. They used heaters to try to free the valve, but those efforts were unsuccessful both before the lunar flyby and in the months after. “As far as we can tell, that valve is very, very stuck.”

Those efforts are continuing, but he said time is running out to try and get LunaH-Map’s thrusters working. “If we cannot ignite the system, we are likely to end operations at the end of May.”

As something of a last-ditch effort to open the valve, controllers are raising the temperature of the overall propulsion system to vaporize more iodine and build up the pressure. “At some point, we may burst through the valve, which could be good or could be very bad,” he said. “It’s really all we have left to try at this point.”

The propulsion system is the only spacecraft system not working, Hardgrove said. “If we didn’t have to wait over a year, I think we would at least have had a chance at conducting our full science mission.”

That mission involved going into an orbit that would take the spacecraft close to the lunar south pole, using a neutron spectrometer to map the presence of hydrogen linked to water ice deposits there. He noted the mission did test the spectrometer during the November lunar flyby at higher altitudes.

LunaH-Map was one of 10 cubesats launched on Artemis 1, many of which suffered varying degrees of technical problems. They ranged from the propulsion system problems on LunaH-Map to spacecraft that were never heard from after deployment from the SLS or lost contact shortly afterwards.

“For some of these missions on Artemis 1, we had to abandon the mission,” said Dan Grebow, a former JPL engineer now at mission design and navigation firm Nabla Zero Labs, during a panel discussion at the conference.

He gave the example of NEA Scout, a cubesat that was designed to deploy a solar sail and go to a near Earth asteroid, but was never heard from after launch. He said the project gave up after not hearing from it, rather than continue to seek Deep Space Network time that could instead be used by other missions. “At some point, you need to know when to let go.”

Hardgrove, also on the panel, defended the cubesat missions flown on Artemis 1. “Characterizing any of them as a failure is not fair,” he said. “They’ve all developed a substantial amount of technology.”

“Many of these missions came very close to being successful,” he said. “Throwing the whole thing out is not fair.”

Related

ncG1vNJzZmiroJawprrEsKpnm5%2BifKK%2B056koqtdZnqkwcGeqpqsXaOyor7Ip55mnZ6ZerCyjKagrKuZpLtw